Classical - Greek & Roman Innovations

|

-

About this Collection

The buildings of the Athenian Acropolis, along with Rome's Pantheon and Colosseum, are magnificent examples of the Classical style--the collective term describing the architecture of ancient Greece and Rome.

The Greeks developed rational, clearly defined forms and rules of use for such elements as columns, using proportions based on the geometry of an ideal human body. The Romans adapted these rules and contributed additional innovations such as extensive use of arches and domes.

After being all but lost during the Middle Ages, these forms and rules, especially the Roman ones, were rediscovered by Renaissance architects. From that time on, Classicism has been one of the most studied, imitated, and adapted concepts of western architecture.

-

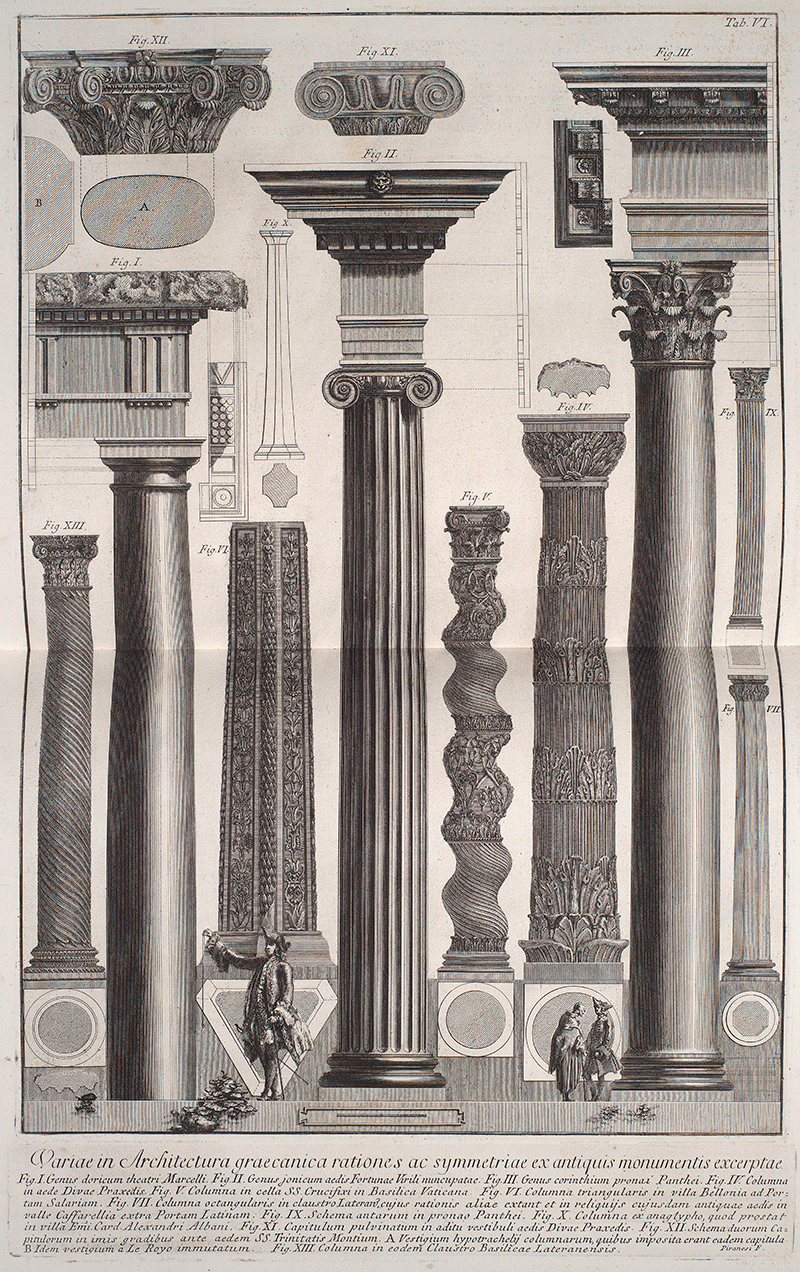

Piranesi presents columns of various classical buildings in a double-page spread

This huge double-page folio image presents columns of various classical buildings, including the Pantheon. Note the architect in 18th century dress using a plumb in the lower left.

This spectacular copperplate etching appears in Giovanni Battista Piranesi's Della magnificenza ed architettura de' romani, published in 1761. This sumptuous volume was Piranesi's major contribution to the scholarly debate that was then raging on which architectural legacy was the more pure and noble, Roman or Greek. Piranesi was a prominent advocate of Roman superiority.

-

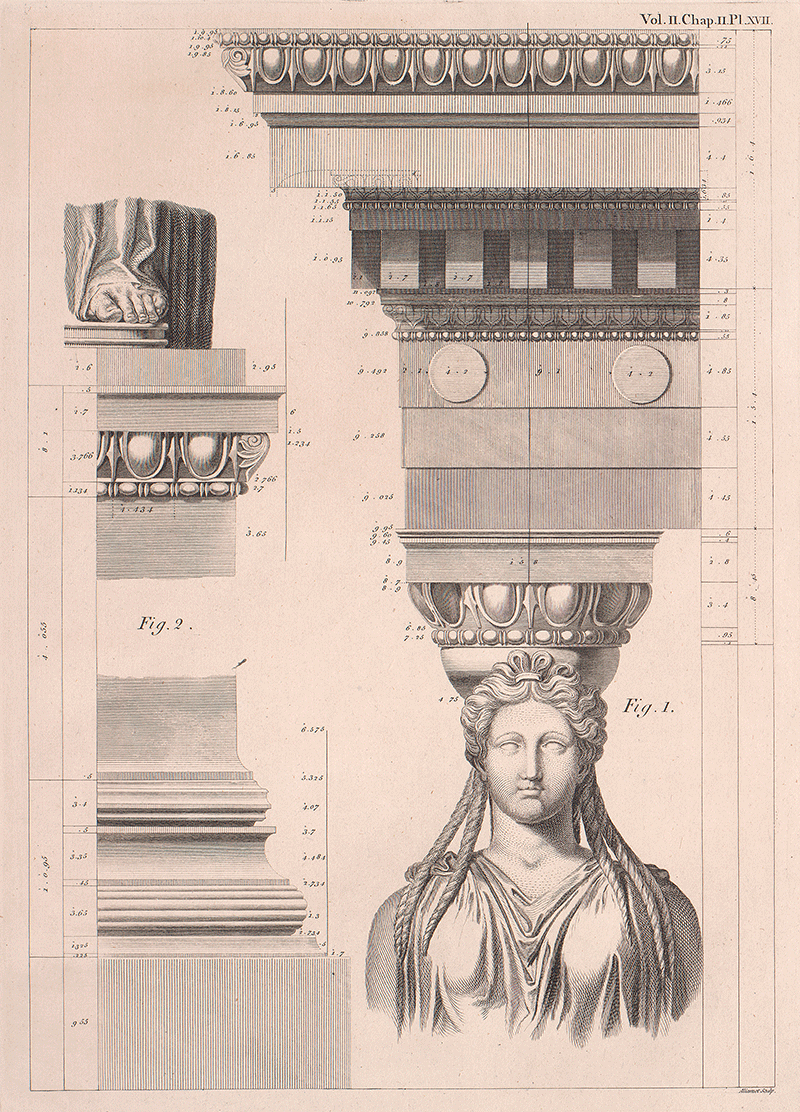

Caryatids of the Erechtheion on the Acropolis from The Antiquities of Athens

Stuart and Revett's detailed elevations of the Caryatid porch of the Erechtheion, a small temple on the acropolis comprising several shrines to Athenian heroes and gods. Caryatids are columns in the shape of women.

-

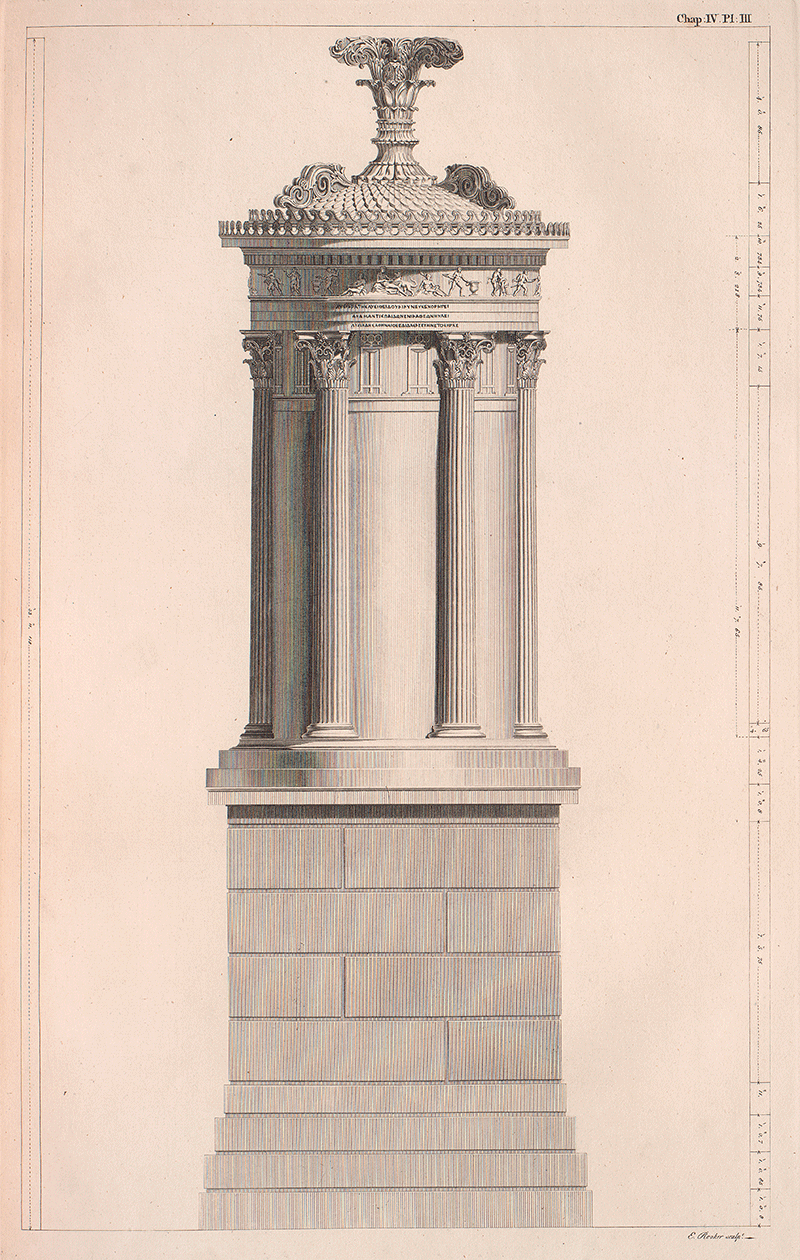

Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens

The Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, 335 B.C., as it was shown in Stuart and Revett's The Antiquities of Athens of 1762.

Choragic monuments were erected in ancient Greece to commemorate victories of the leaders of choruses in competitions. This graceful circular structure is perhaps the most well known of these monuments, and represents one of the earliest known uses of the Greek Corinthian order.

-

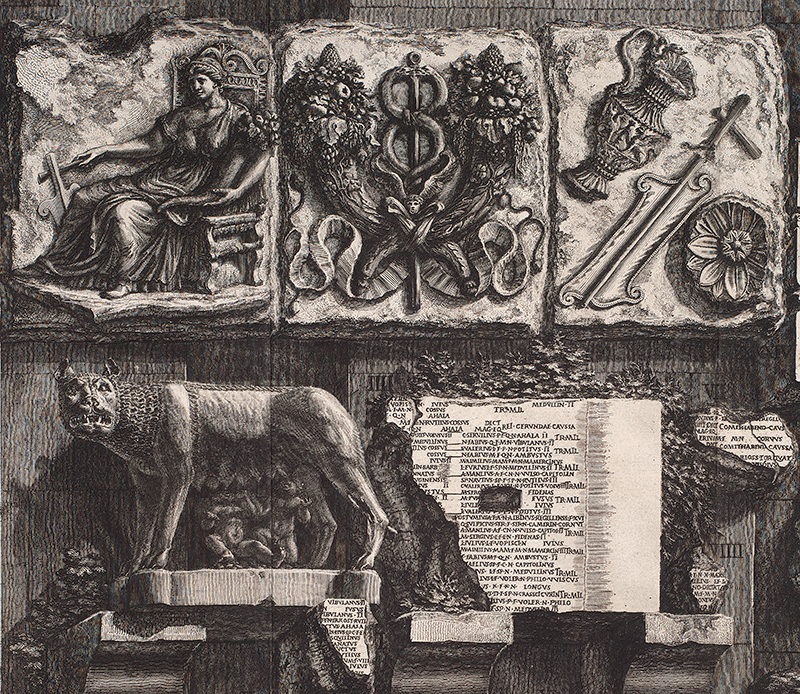

Detail of a 5-foot foldout of inscriptions found in the Roman Forum

Detail of the 5-foot foldout plate from Giovanni Battista Piranesi's Lapides Capitolini of 1762.

These ancient inscriptions had been found in the Roman Forum, and were displayed in a large frame on the Capitoline Hill. Piranesi interspersed fragments of sculpture and bas-reliefs into his composition, some of which are shown here. The statue of the wolf nurturing Romulus and Remus, the mythical founders of Rome, can still be seen today in the Capitoline Museum.

-

Dramatic covered gallery, or 'crypto-porticus', of the Palace of Diocletian

Robert Adam was anxious to prove to the aristocracy of Great Britain that he was a bona-fide antiquarian as well as a talented architect. This was done at that time by studying, documenting, and publishing sumptious engraved folios describing archaeological sites. During his stay in Rome, he discovered that the ruins of a late Roman palace were still undocumented. He hired a team of artists, and traveled to the city of Spalato (present-day Split) on the eastern Adriatic coast (present-day Croatia). He and his team spent 5 weeks there, and the results were published in 1764 as The Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia.

The long dramatic covered gallery, or 'crypto-porticus', of the Palace extended along the entire southern façade of the palace and overlooked the Adriatic Sea.

-

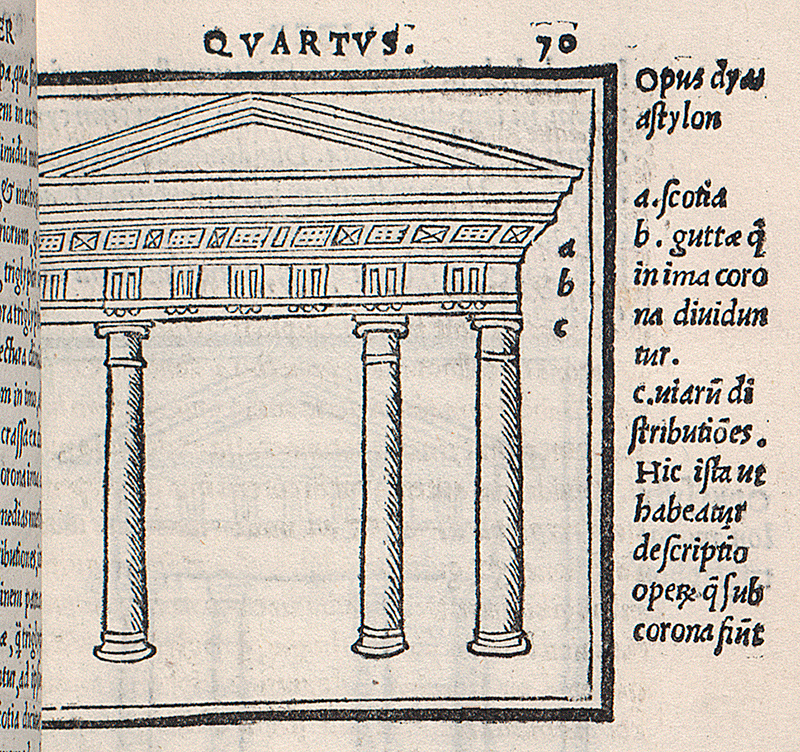

Facade of a classical temple from the 1522 edition of Vitruvius

This page illustrates some of the features of the small-sized octavo books that were becoming popular in the early 16th century. They were small enough to fit into a hand and printed in Italic typeface.

Illustration of a temple facade from the Steedman's 1522 octavo edition of Vitrivius' 'Ten Books of Architecture'.

This image of four columns holding up a pediment is more primitively rendered in this handbook edition than in the folio 1521 edition.

-

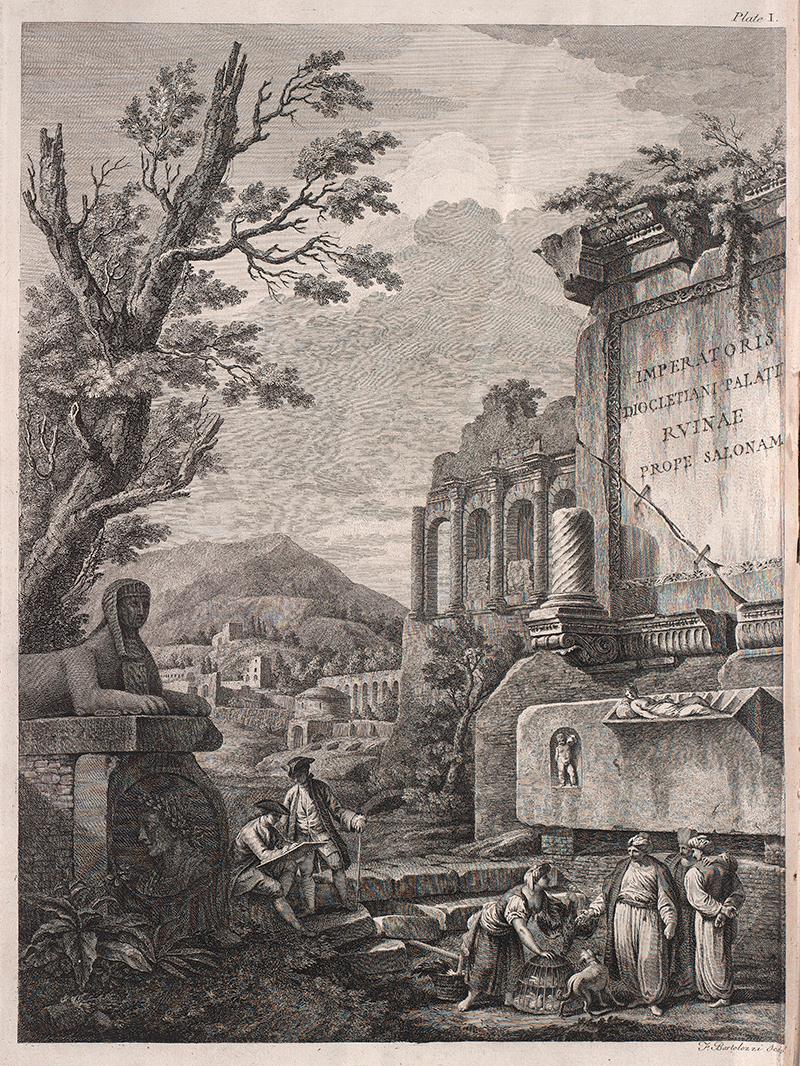

Frontispiece depicts the researchers in their mid-18th century dress earnestly drawing the ruins

The frontispiece of Robert Adam's The Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia of 1764. It depicts the European research party in their mid-18th century dress earnestly drawing the ruins.

The residents of the town, which had grown up in and around the sprawling ruins, are pictured in their style of contemporary clothing. The area was ethnically Slavic, although it was then under Venetian rule.

Adam and a team of artists traveled to the city of Spalato (present-day Split) on the eastern Adriatic coast (present-day Croatia) to research and document this late Roman palace.

-

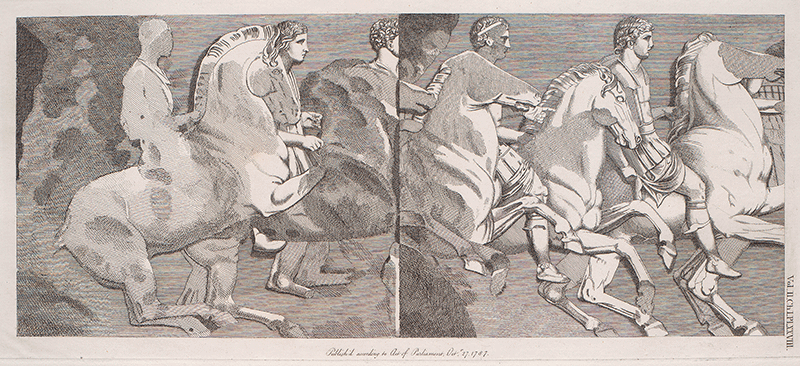

Parthenon frieze from The Antiquities of Athens

Stuart and Revett not only recorded the architectural plans and construction of ancient Athens, but also carefully drew the embellishments of the buildings.

This is a section of the Parthenon frieze depicting the Panathenaic procession, a part of the ceremonies for a festival that occurred every four years.

The sculptures from the Parthenon were taken to London by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century and can be seen today in the British Museum.

-

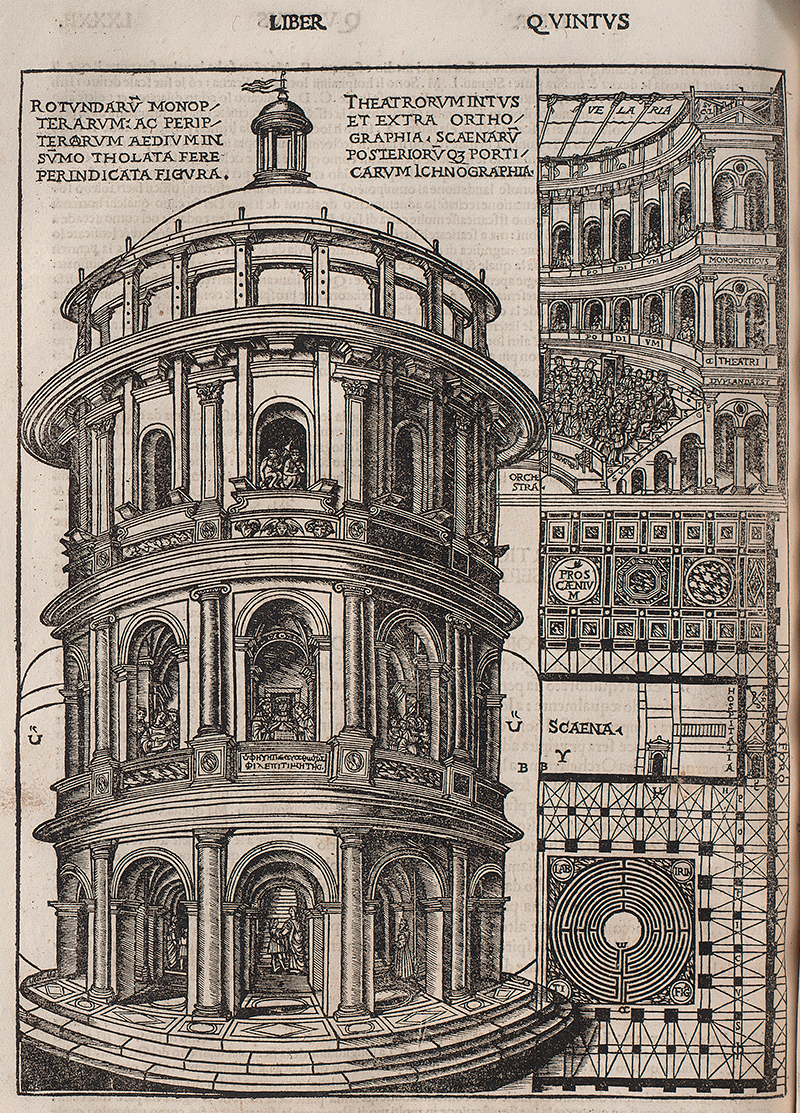

Roman theaters from the 1521 edition of Vitruvius

A Renaissance artist's rendering of Vitruvius' description of ancient Roman theaters.

Note the labyrinth in the lower right.

-

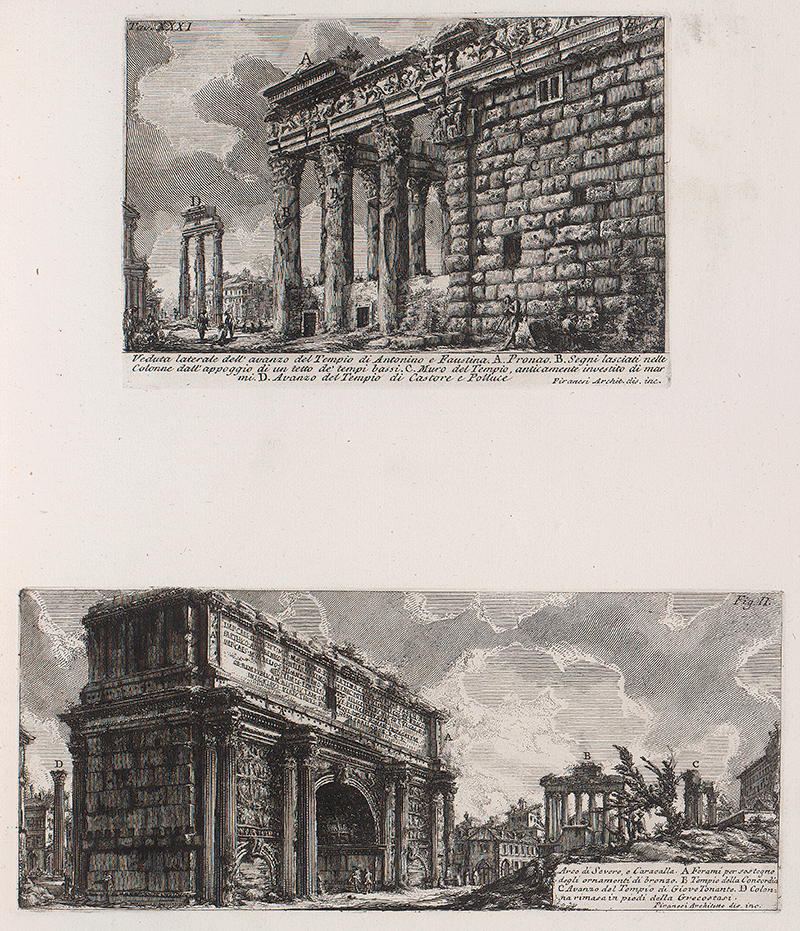

Ruins in the Roman Forum as etched by Piranesi in the 18th century

Views of two ruins in the Roman Forum as they appeared in Piranesi's time. Above is the Temple of Antonino and Faustina, and below is the Arch of Septimius Severus. Only the top portion of the Arch was still above ground at that time.

This etching appears in Giovanni Battista Piranesi's four-volume Antichità romane, published in 1756.

-

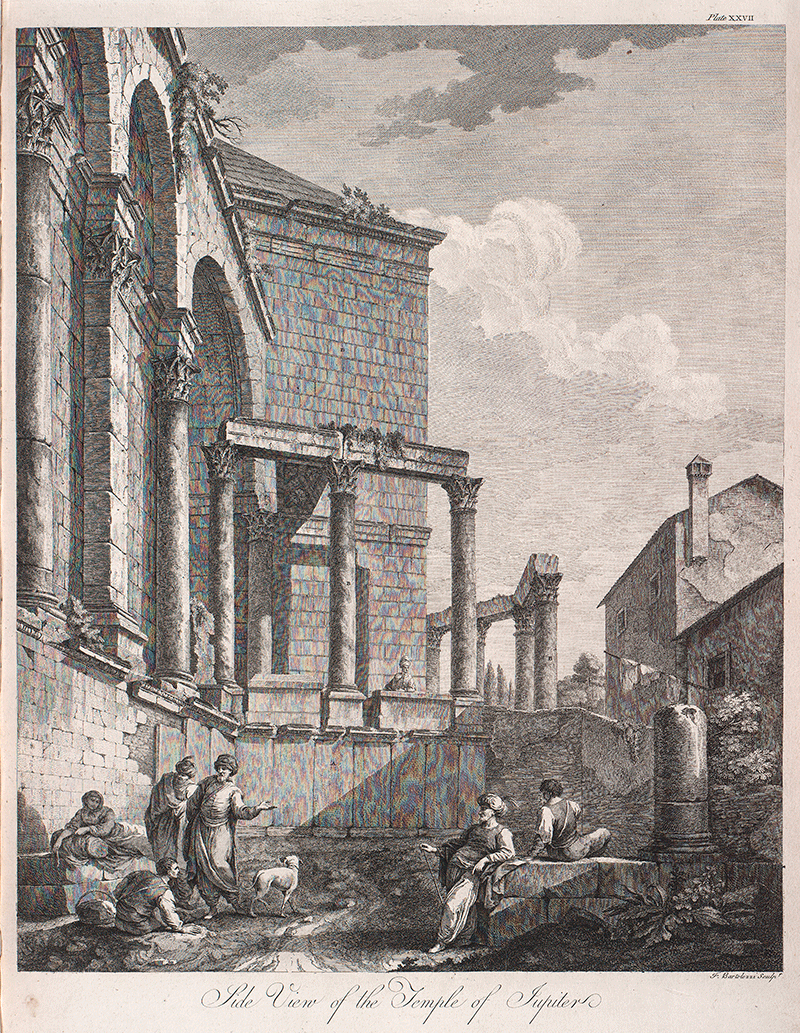

Side view of the mausoleum at the Palace of Diocletian, 1764

Robert Adam was anxious to prove to the aristocracy of Great Britain that he was a bona-fide antiquarian as well as a talented architect. This was done at that time by studying, documenting, and publishing sumptious engraved folios describing archaeological sites. During his stay in Rome, he discovered that the ruins of a late Roman palace was still undocumented. He hired a team of artists, and traveled to the city of Spalato (present-day Split) on the eastern Adriatic coast (present-day Croatia). He and his team spent 5 weeks there, and the results were published in 1764 as The Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia.

Adam erroneously identified the Palace of Diocletian's mausoleum as a Temple of Jupiter. In this side view, the current state of the structure is documented - plants growing from it, contemporary houses next to it, local residents conducting their daily business in its precincts.

-

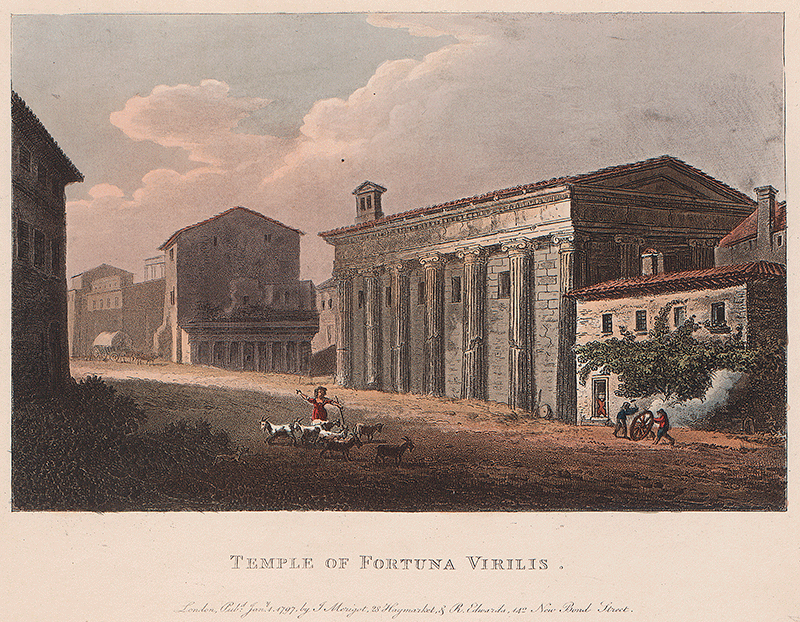

Temple of Fortuna Virilis in Rome as it appeared in the late 18th century

The Temple of Fortuna Virilis as it appeared in the late 18th century.

This image is from a lovely compendium of delicately tinted aquatints produced by J. Merigot in 1791. Entitled The Ruins of Rome, it depicts ancient Roman structures as seen by travelers on the Grand Tour.

View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image