Letting in LIght

|

-

About this Collection

The earliest windows were merely openings that let in light and air. Differences in cultural tastes, improved technologies, and architects’ creativity have influenced the evolution of window design.

The ancient Romans were the first to use small sheets of glass (panes) over openings. But it was not until much later, when glass production techniques were improved, that architects and engineers could increase the size, number, and look of a building’s windows.

By the Gothic period (ca. 1000-1400) available technology allowed production of larger glass panes and the development of colorful stained glass.

An arch flanked by upright rectangular shapes. which became popular during the Renaissance, is called a Palladian window.

In more modern times, advances in heating, cooling, lighting, and glass strength added flexibility. Windows did not have to open, were not the only source of light, and could be almost any size. Larger buildings used tinted glass or mirror windows to give an illusion of transparency and allow stunning views.

From uncovered openings to modern tinted glass curtain walls, the purpose of windows remains much the same— providing natural light in the buildings where people work, live, or worship.

-

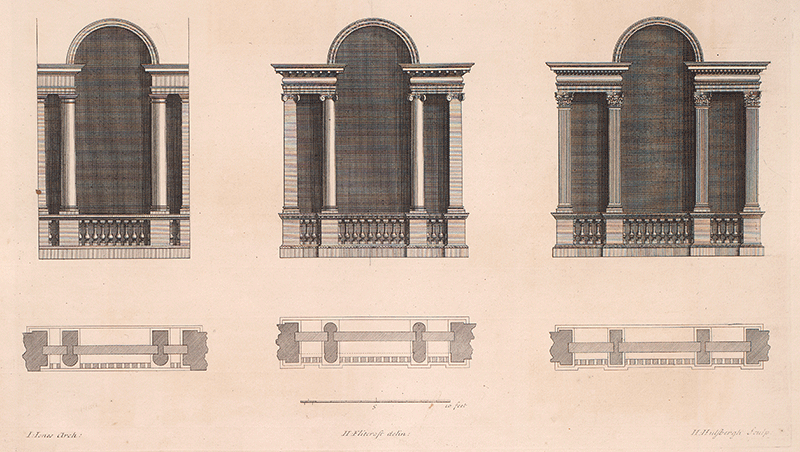

Venetian windows depicted in Kent's Designs of Inigo Jones

This plate of three 'Venetian' windows depicts what is now known as 'Palladian', or 'Serlian' style: one large arched window flanked by smaller rectangular windows, using prescribed proportions.

William Kent's book on Inigo Jones, published in 1727, was influential in changing British architectural taste from the Baroque to Neoclassical.

-

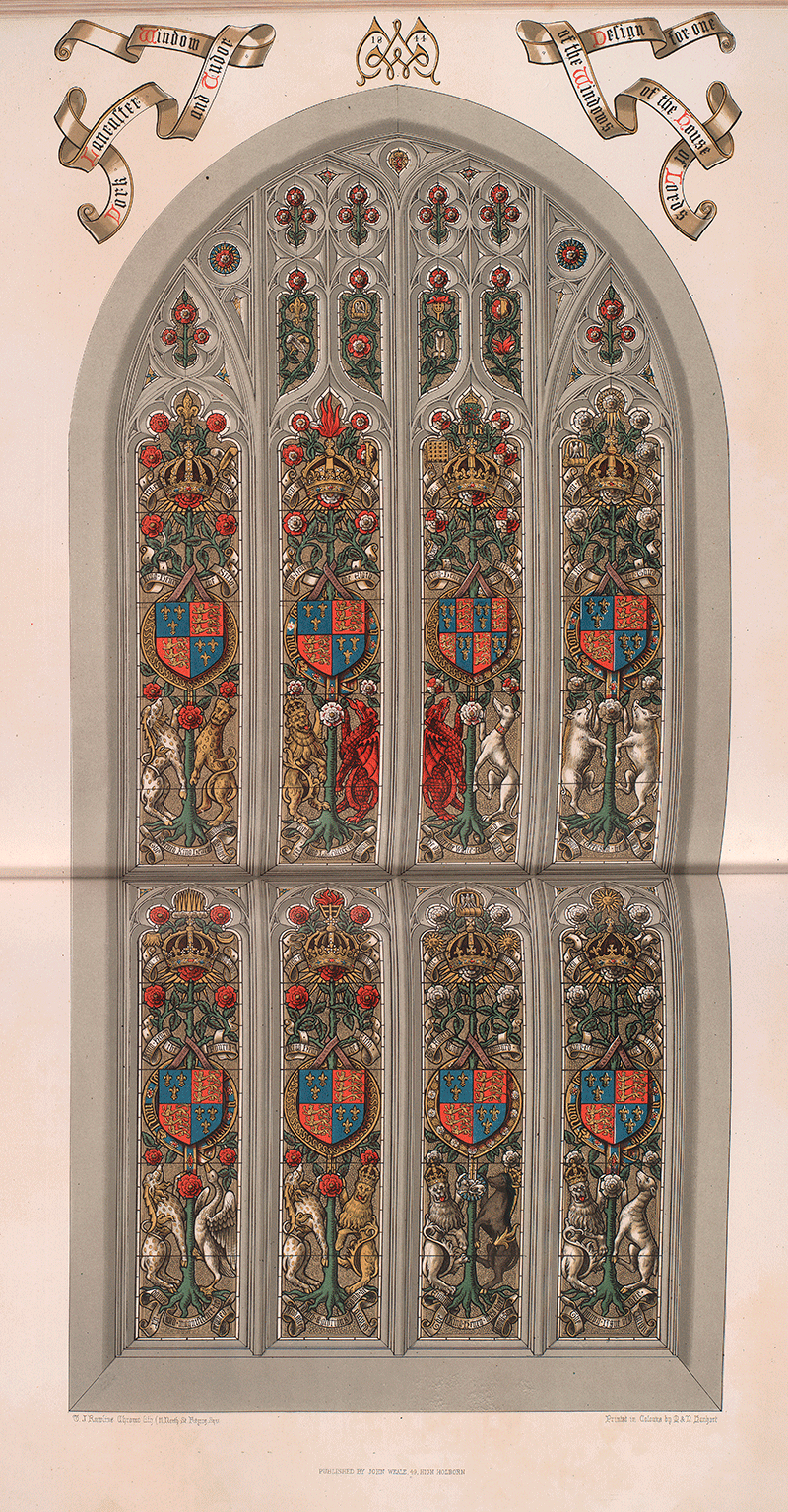

A design for 'York, Lancaster and Tudor Window' for the British Parliament's House of Lords

This image is from The History of Stained Glass, from the Earliest Period of the Art to the Present Time by William Warrington, of 1848. This large-format folio edition with color lithographs illustrated British stained glass window designs from the 11th to the 15th centuries. Of later works, the author states, "...styles (if they may be so termed) differing so much in all respects from medieval works, ...have been a misconception and misapplication of this art."

Early in his career, A. W. N. Pugin used Warrington to make the stained glass for his buildings.

-

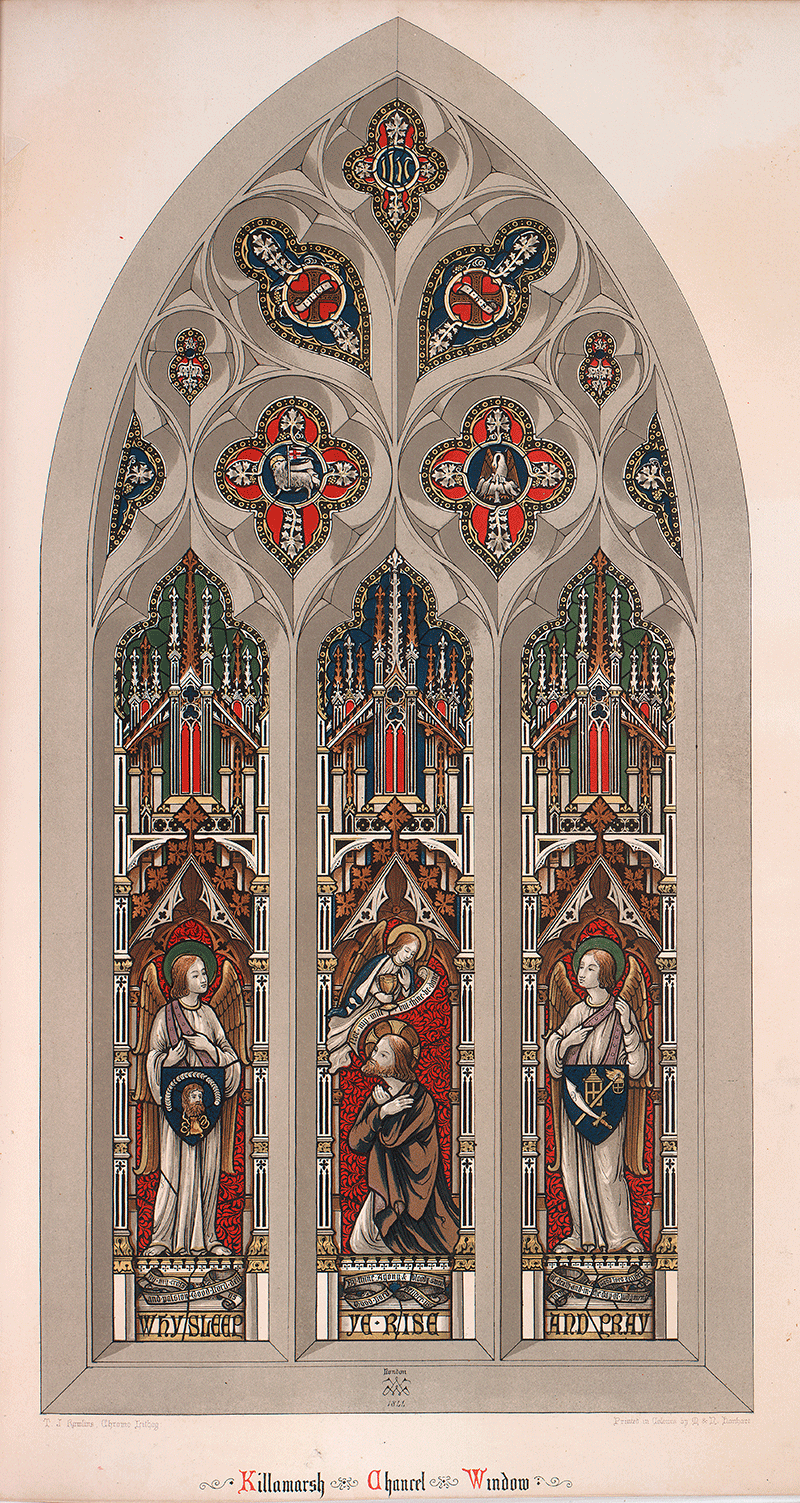

Design for a window in the style of the 14th century in the town of Killamarsh

This image is from The History of Stained Glass, from the Earliest Period of the Art to the Present Time by William Warrington, of 1848.

Warrington was an associate of famed Gothic Revival architect and theorist A. W. N. Pugin.

-

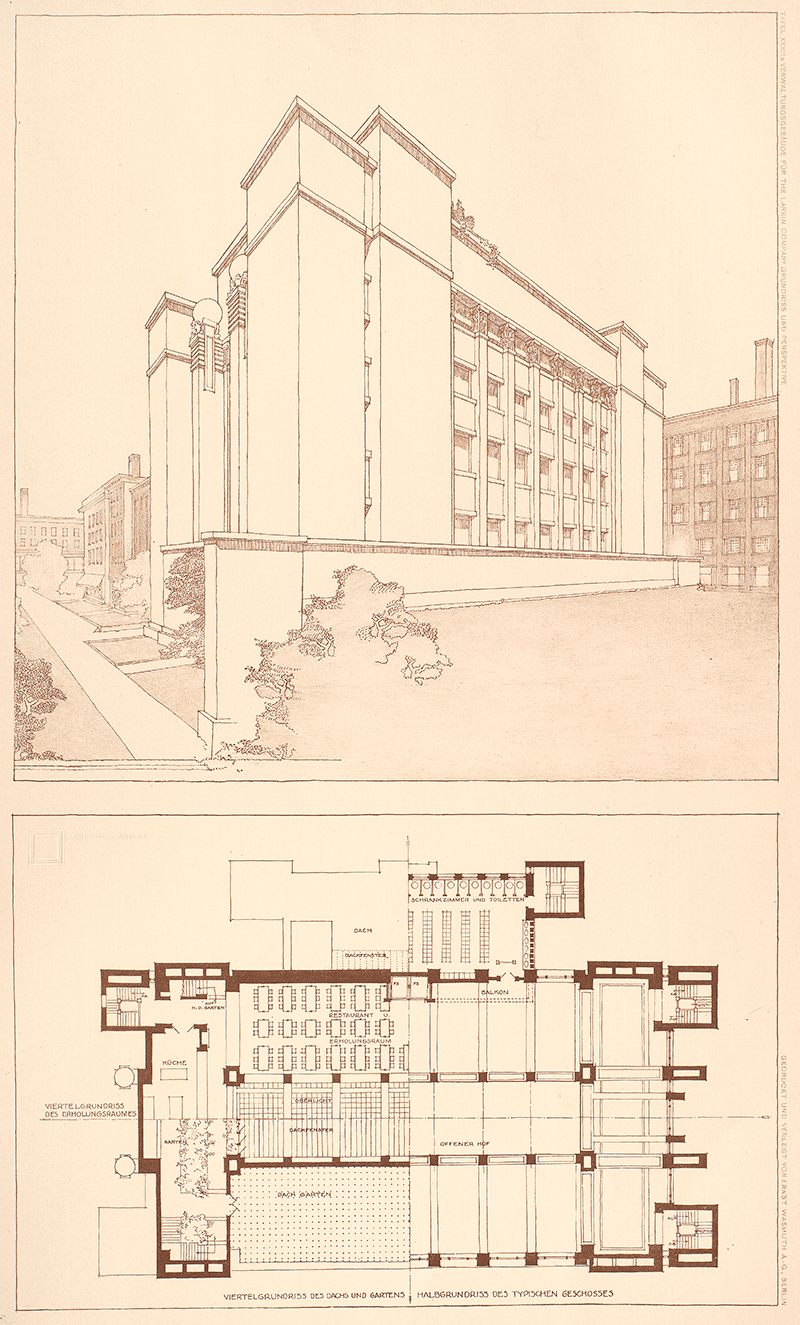

Frank Lloyd Wright's Larkin Building in Buffalo, New York, 1902

Exterior view and ground plan of the Larkin Company administration building in Buffalo, New York, designed in 1902 by Frank Lloyd Wright.

Wright later claimed that with this building, he successfully broke away from designing boxes for the first time. For this commercial building, he used vertical lines and a large centralized interior space. Wright's ornamentation, or lack of it, was a conscious rebellion against the prevalent use of revival styles in the United States, such as those practiced by Daniel H. Burnham. The building was demolished in 1950.

This plate is from the Wasmuth Portfolio of Wright's work (1910).

-

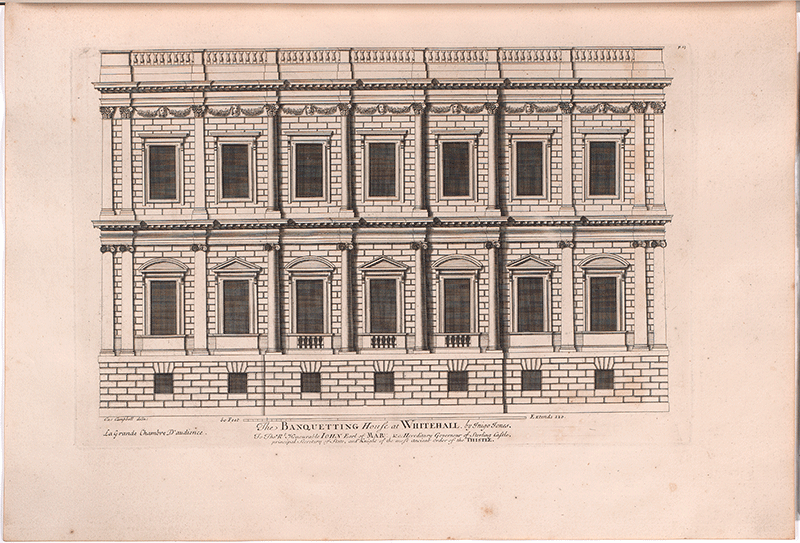

Inigo Jones' Banqueting House in Whitehall, as pictured in the Vitruvius Britannicus

This building is perhaps Inigo Jones' most well-known building, prominently situated on London's Whitehall across from the Horse Guards. Designed by Jones for King Charles I nearly a century earlier than this publication (around 1620) it was the first example of proper, restrained classical architecture in Britain, and is held up by 18th century British neoclassicists as the supreme example of this style.

This illustration appears in the Vitruvius Britannicus of 1715.

View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image View Image

View Image